Art and Terrorism: Face-to-Face

The Aesthetics of Death:

The terrorist organization of Islamic State (ISIS) had astonished the world, not only with its rapid spread and penetration into the geographies that it swiftly controlled, but also through its techniques, tools, and artistic skills that are comparable to Hollywood films when it comes to the quality of plot and direction. But instead of having actors playing the roles that were written for them, the organization made it more real and bloody by making the “heroes” from within its members; while the “bad guys” were the captives and the kidnapped. The acting course had become more realistic, in fact, from real flesh and blood, and the cinematic “killing” process had become a real and “tangible” process; this made the “artistic” aspect to take a terrorist dimension rather than an aesthetic one.

The acting course had become more realistic, in fact, from real flesh and blood, and the cinematic “killing” process had become a real and “tangible” process; this made the “artistic” aspect to take a terrorist dimension rather than an aesthetic one.

Therefore, we find ourselves before the “Aesthetics of Death” [1], as the picture is no longer a tool for creating life from a captured moment in the past, but rather it has turned into a mean to generate death from life and death itself. From this point of view, today, pictures on television and the internet constitute a strong support for the “terrorist” to promote the “pictures of death” through a dazzling aesthetic form, using high-quality tools and visual effects that are intended to fascinate and deceive the viewers. Fascination, as written by G. Cohen in his book (L’action sur L’homme), is “the power of visual media, due to the presence of individuals who are deprived of the means of distance and perception.” The deception here “is [how] the viewers lose their intellectual autonomy, in their voluntary or involuntary surrender to the dynamics of pictures, in a process in which thought does not participate in.” [2]

After the fatwas of the extremist movements were aimed at prohibiting the picture [3] and considering them “outrage from the work of Satan”, they became an analytical and effective tool in the hands of “terror / terrorist”. The extremists, then, possessed the “picture” and with it they gained some level of “art”, not for the benefit of humanity, but to serve their interests through professional propaganda. This prompted the late thinker Salāmah Kaylah to say that: “Everything that ISIS circulates is the product of an international company, not the product of ‘jihadists’ at all. [As if] a professional international company is shooting a movie that could be released under the name ‘ISIS’. The ‘jihadists’ themselves do not have such capabilities in photography at this level.” [4] Perhaps Salāmah Kaylah did not notice a key point in the history of the jihadist organizations, which transformed their recruitment of fighters and members from Arab countries – the marginalized and the vulnerable – into the luring of individuals from Western countries who have a high training in specialized and advanced institutes. Among which are the audio-visual institutes that have practice in directing, montage, and etc. The ground work for this matter began since the so-called “Universal Jihad” [5] in the last decade of the last century with al-Qaeda organization. [6] Therefore, these movements and organizations are no longer in a “conflict with the picture” as long as it serves their interests, and since they have shifted from prohibiting [the picture] to the objectionable use which is permitted; or according to Ibn Baz’s words: “Picture is reprehensible and forbidden, unless it is necessary. In that case, a person is considered in a state of necessity as compulsion.” Or in other words, as long as [the picture] is in the service of “the Aesthetics of Death,” [it is necessary].

Art in the Face of Death:

The subject of death has occupied the minds of artists throughout the ages. Rather, it was one of the most important and widely discussed topics. This prompted the late Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish to say in his immortal mural: “I defeated you, O death of all arts.” It is, then, a relationship of struggle between conqueror and the underdog that combines art and death, between the quest for immortality and the gateway to annihilation. [7] This is why Gilles Deleuze tells us that there is a type of “basic emphasis between a work of art and an act of resistance”. [8] But what kind of resistance? “Resisting death,” he replies. From this point of view, a group of Arab artists who comprehended the transcontinental “terrorist” invasion of Arab countries, embarked on works and topics that seek to combat and resist this dark tide, with the colors, ideas, shapes and bodies available to them.

We are therefore facing a conflict between discordant forces, which have never been overlapping or close together; each party to the conflict is a sworn enemy of the other. Today, extremist movements have exploited art techniques for the benefit of their discourse and their “picture.” They do not base this exploitation on an “artistic” or humanitarian ground, rather, considering these technologies as mere means to serve their interests and bloodshed, to terrorize and intimidate the different other. While the artist seeks to reach the aesthetics of “human sense”, touching on the [idea of] “the universe within the man” which does not intend to differentiate despite ethnic, linguistic and religious differences.

Today, extremist movements have exploited art techniques for the benefit of their discourse and their “picture.” They do not base this exploitation on an “artistic” or humanitarian ground, rather, considering these technologies as mere means to serve their interests and bloodshed, to terrorize and intimidate the different other.

Art for Peace

Under a common global vision of peace, Moroccan artist Rachid Bakhouz worked, through his chromatic and structural letters, on the issue of coexistence between cultures, religions and languages in an attempt to ward off all fundamentals of extremism. The creative influence of this artist, especially his installation work – No Title – is seen (in the Bab Al-Kabeer Exhibition, 2016), where letters in Arabic, Latin and Hebrew hang from sticks over ashes. This makes me say before several questions such as: Is the world becoming the “death of civilization” (Fukuyama), the “clash of civilizations” (Huntington), or the “human civilization” (Todorov)? This artist tends to the latter, considering that human future moves towards a single civilization, a human civilization in which all human beings, with their identities, cultural and linguistic differences, coexist and seek peace.

As for his installation “Transcendence” – which he presented in the exhibition “Between the Visible and the Invisible” (Villa des Arts, Casablanca 2018) – Arabic, Latin and Hebrew letters in it have taken spiral and intertwined shapes to reflect the art through symbolic and aesthetic connotations in a way that transcends the earth in the higher direction – a reference to the rise of civilizational conflicts related to linguistic, identity and theological discourses. As for the installation “Faraka [renovation]” and the art video “Faraka 2” (at the same exhibition), in it, Rashid Bakhouz calls for the need to reconsider the linguistic discourse circulating in Arab geography, especially extending from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf with all its ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity (Islamic, Christian and Jewish); that appears to be why it was necessary to clean the letters (rubbing and washing them), spreading and drying them, in order to sensitize an interactive civilized dialogue between cultures. The installation combines Arabic, Hebrew and Latin letters in an aesthetic work based on a universal vision of tolerance and coexistence; all this is through a harmonious presence of the shapes and letters with which the audience interacts to form their own sentences and words inside the exhibition hall.

To him, art is a project to exceed metaphysics that transcend all possibilities of survival, sharing and coexistence in the earth, in order to eliminate nihilism. So, Rashid Bakhouz presents us with works of art full of signs that open up to other signs in an aesthetic web within an endless series of references that the entire human universe can accommodate; a picture of a universal map that hosts all people with their different languages, cultures, civilizations and religions; discarding any perception of conflict or collision, and calling for coexistence, tolerance and peace. For this reason, his letterism is as much as it is contemporary in terms of work and the multiplicity of readings it bears, as it carries with it an explicit and direct call for peace. Through his aesthetic work, Rashid Bakhouz tries to introduce his positions, views, and vision of the world; the artwork has become fertile ground for interpretation that multiplies, grows like a rhizome plant.

A picture of a universal map that hosts all people with their different languages, cultures, civilizations and religions; discarding any perception of conflict or collision, and calling for coexistence, tolerance and peace.

Art and the Struggle for Identity

While the messages that the Moroccan artist, Mounir Fatmi, works on fall within the circle of the death of ideology, the end of dogmatism, deconstruction issues and the question of identity, as well as the question of the current situation that occupies the mind of the Arab citizen with political, religious and cultural concerns; he previously worked on the issue of the Arab Spring in one of his individual exhibitions. He has been also concerned with topics of religious extremism and the Arab/Western identity conflict, the “we” and “them”. It is the conflict on which the discourses of extremist Islamic movements depend, as it derives its roots from the duality of the countries of Islam and the countries of “infidels” (the countries of peace and the countries of war). In most of his works, we see an attempt to overcome this collision, which he tries to tell us that it is an “imaginary struggle” and that it must be transcended towards “an identity that is not clinging to the past, and remains in its thoughts.” When he takes a group of Qur’anic verses and places them in serrated iron circles, their purpose is not to mock the Holy Book, as some have tried to describe the matter; rather, it is an attempt to pass on the message of the fact that these verses, after their long, ideological interpretation by observers over time (according to the multiplicity of sects and their ideas), have acquired sharp edges and deadly explanations. This is what generated this conflict that must be overcome. However, this will only be done by scraping and removing those canines, and the matter becomes clear in the performance that was previously presented under the title: (Paradox), as it rotates the razors.

In response to the conflict between the “The Arab Me and the Western Other”, which is still being exploited by jihadist organizations, Fatmi presented his show entitled “Saving Manhattan (01/02/03)”, following the background of what the city of Manhattan experienced in 2001 or what was famous for the events of 9/11, which fueled this conflict and the subsequent wars in the East, and the earlier policies and revolutions that took place there. “What is distinguished in this repeated experience of Mounir Fatmi” – as the writer Talal Qasumi tells us – is that “it was presented in different perceptions, and the materials employed in the artwork were the source of the differences. The artist has sought to observe this incident according to the developments in the interaction of the world events, trying to reveal and expose the essence of the actions that followed it. Despite its repetition, this work carries the same idea based mainly on the interpretation of reality and its presentation in a manner that elevates the event to the level of creativity.” The artist presented his show (Structural / Shadow) by placing a group of books that explained the events of 9/11 and its aftermath, as well as a group of Islamic religious books, including two copies of Qur’an, shining a strong light on the [religious] books. What forms through the shadows of the Manhattan towers and the city, and its use of religious books is nothing but an indication of the interpretive background from which the perpetrators of these events started.

The artist has sought to observe this incident according to the developments in the interaction of the world events, trying to reveal and expose the essence of the actions that followed it.

Mounir Fatmi, through his work and research contrary to the prevailing tradition, was able to give his works the characteristic of surprise and shock, through which he tries to express his thoughts about the “imaginary conflict.” He also put the question of identity into the subject of revelation in an attempt to renew the vision about ancestry and heritage. Thus, creating a new debate in the bilateral relationship between the artistic effect as an act in history and reality, questioning reality through the creative act emanating from modernity and its essence.

Dance vs. Terror

Apart from the works of fine art, the Syrian dancer, Ahmed Joudeh, works on making dance and the body a weapon in the face of terrorism. The art of dance is based on the superiority of the body over the rest of the other arts, as the body alone is present as an artistic singular. If we fall short of saying that it is an integrated work of art, then as the artist resorts to dancing as a weapon in the face of extremism, he works to strip the body of discourses of prohibition and incrimination, liberating it from the “theological” restrictions that demonize it instead of elevating the soul. In this sense, dancing sanctifies the profane (the body), the Islamic jurisprudential discourse is trying hard to put shackles and rules for the body, that ‘you do not have a free body’, as it is in the service of the community, and every liberating process calls for the punishment of the body – “We are our bodies.” [9] The French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty tells us: “My presence in the world begins with two bodies. Rather, I recognize the world, and it recognizes me through my body.” For this reason, dancing is considered a rebellion against the “teachings of Islam,” according to scholars. As religion codified the body and controlled all of its movements from awakening to sleep, therefore, when Ahmed Joudeh dances, he threatens the power and authority of this organization and others, undermining its existence by spreading an artistic visual discourse that says “Dance and liberate.”

The French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty tells us: My presence in the world begins with two bodies. Rather, I recognize the world, and it recognizes me through my body.

The [ISIS] organization responded as they spoke to the artist, saying that: ‘They shall shoot him in the leg so he cannot dance.” This made the artist to escape his homeland Syria and his city Damascus, fleeing with his body safely for the sake of his art, and to face the new “ISIS weapon” (the picture) even outside the country. This is in a Nietzschean vision that blesses both the body and dance; for him, dance is the shining expression of willpower and the “eternal return.” He says through the lips of the hero of his novel, Zarathustra: “I am not expressing the highest meanings with symbols, except when I am spinning in dance, so my body parts were unable to draw the most wonderful symbols with their movements, and I aspired one day to dance, transcending my art beyond the seven layers.” In the philosophy of dance, Nietzsche turns to his main concept of the will, which asserts that: “There is no will except where life manifests itself.” We see these Nietzschean dimensions in Ahmed Joudeh’s blatant saying: “Either you dance or you die!”

Dancing, then, offers an escape from death and a reason for life, and Ahmed not only faced the terrorist regime, but also faced the conservative society represented by his father, who did not see in dancing anything but an art that is not worthy of men. Thus, this artist is resisting extremism at one time and the conservative societal vision at other, and after his success in escaping from the brutality of the ISIS organization and leaving the Yarmouk camp, fleeing to Europe, he was able to reconcile with his father and accomplish works that advocate for peace. In 2017, the young man danced in the Human Rights Square on Trocadero Avenue in the French capital to deliver a message of peace to the tune of a song specially composed for this show.

Cinematography of Terrorism:

The terrorists have succeeded in acquiring cinema techniques, exploiting all available and possible technology to make their propaganda films to promote their speech and to attract more vulnerable youth who see in their regime strength, as they are affected by all these visual, sound and directing qualities. Yet the terrorists did not hold art, for art constitutes a threat to them, as a metaphysics parallel to the metaphysics in which they believe in; and as a ground for the hostile and counter discourse that threatens its survival and continuity.

That is why cinematic, dramatic and television works that depend on the subject of terrorism pose an explicit threat to these terrorist regimes. To the extent that “terrorist film making” depends on direct force, intimidation and threats. Drama in the cinematic and artistic fields depends on working within the psychological field, or in a more precise sense, psychodrama. Where all plans are included like: Seeing your face in the face of the other and seeing the other in the face of a third party; this makes psychological drama an experience of liberation from aggression, tension and anxiety [10], in other words, a tool and a means to confront extremism and terrorism.

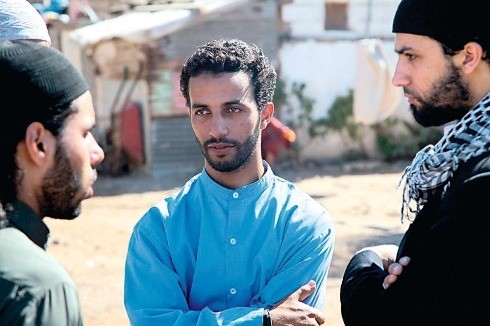

Many Arab films have succeeded in creating a psycho-dramatic atmosphere that exposes the worlds of extremism and reveals their social, cultural, psychological and economic sources, putting the audience in a psychological confrontation that allows them to psychologically discover the characters. Among these films are the Moroccan film “Ya Kheil Allah [Horses of God]” by Moroccan director Nabil Ayouch in 2012; excerpting from the novel “Horses of God (Les Étoiles de Sidi Moumen)” by Mahi Binebine about the terrorist attacks that targeted Casablanca in May 16, 2003. And “Sidi Moumen” is the name of the residential neighborhood from which a group of young people who carried out terrorist acts affiliated with Al-Qaeda emerged. The film tells the story of two brothers, the eldest is a drug dealer and the younger one is a vegetable seller. Their lives are upended after the older brother entered prison and was influenced by a terrorist group. The film shows how these incidents drive the younger brother to follow his brother’s example and join the group, and then carry out a suicide attack.

Other Arab films since the 80’s of the last century have succeeded in addressing the phenomenon of terrorism, dismantling its origins, and putting the audience before its bloodiness, violence and danger to society; films such as “The Terrorist 1994”, “Toyour Elzalam 1995”, “Dam El Ghazal 2005”, and “The Embassy Next Door 2005” – they are films that discuss various topics such as the issue of IEDs, terrorist operations, intimidation, violence and discrimination in different psycho-dramatic plots.

In conclusion, art is a weapon:

Therefore, we have nothing but art as a weapon in our hands to confront terrorism and extremism, which have become more and more penetrating among us, threatening us by using techniques that artists have kept for themselves and their creative artistic activities. The terrorists have become more sophisticated and modern in their weapon and picture, so they realized the role of the latter in stirring feelings and playing on the psyche of the audience and making them more attracted to the discourse they promote. Previously terrorists attempted to forbid and intimidate the “picture”, today they exploit it to serve their interests, and we can only confront this by beauty and aesthetics; by making art at the service of exposing the reality of these organizations and revealing the violence and destruction they inflict on the whole world, and how urgently we need today to understand “the aesthetics of ugliness”, where aesthetically “forsaken” standards become criteria for creating works of art that carry multiple interpretations. Ugly is central to aesthetics, or, as Friedrich Schlegel puts it, “Ugly is the dominant and total characteristic of character of the individual, of the interesting, of the research which is neither convincing nor content with anything new, scathing, or astonishing.” [11]

The terrorists have deliberately disrupted our concepts, and they depict and display ugliness, and win through it and attracts to their core new supporters and enthusiasts. That is why J. Baudrillard dared to express the aesthetics of the destruction of the Twin Towers of Manhattan. Today, we have to recycle this “ugliness” for our artistic benefit, depending on the psychodrama, and the feelings it produces within the audience, as well as by confronting terrorism and terrorists with art in body and picture, and taking art out into the street.

Today, we have to recycle this “ugliness” for our artistic benefit, depending on the psychodrama, and the feelings it produces within the audience, as well as by confronting terrorism and terrorists with art in body and picture, and taking art out into the street.

References: