“No room for hatred”

“No room for hatred”

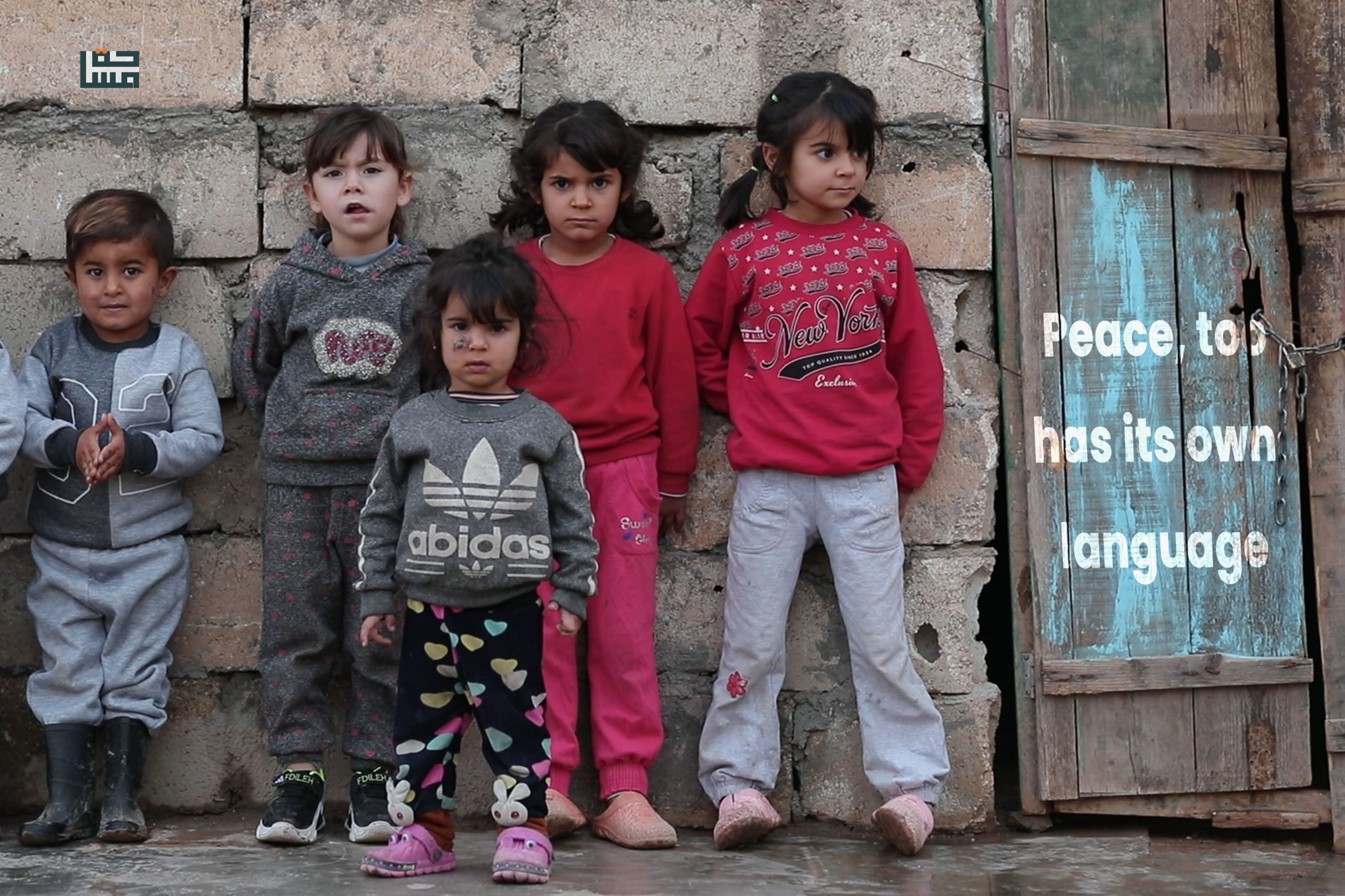

It is a diversity that reflects the colors of love and embraces a peaceful harmony which brings everyone to the horizons of intimacy. It is a world filled by kindness and peace; the Kurdish-Christian coexistence.

Disturbing winds

In the sixties of the 20th century, a dark and lonely day in the village of Sarmsakh Tahtani: Syrian government forces attack the villagers to force them to sign papers that renounce the ownership of their homes and lands in favor of the “Al-Ghamr” displaced people – Al-Ghamr are the Arabs whose lands on the banks of the Euphrates River were taken by the Syrian government, and then they were settled in Kurdish areas on the Syrian-Turkish border. The people of Sarmsakh Tahtani objected to the construction of fences around the village which was meant to separate it from the surrounding areas, such as the village of Sarmsakh Fawqani. As a result, the Syrian authorities arrested six of the residents and imprisoned them. However, the same authorities withdrew from the settlement decision after facing the Kurdish-Syriac solidarity there. Relinquishing their lands meant abandoning their common history rooted in their collective memory. Their memories were a shared homeland and the gathering of their harmonious souls in a picture much broader than their neighboring homes in the village and greater than their agricultural lands. The Syriac-Kurdish harmony was therefore embodied in their unity in the face of disturbing winds.

Extremism inflamed the universe to the point of turning it into a pile of debris. It silenced all the languages of the world and shortened them through its violence. Breaking news displayed the blood of the victims of the mad extremism on its news broadcasts. It is the image of the world whose terrible noise fades in the words of Wadih Iskandar, who comes from the village of Sarmsakh Tahtani, west of the city of Derik in northeast Syria. “Difference in religion does not change our lives as Syriacs with our Muslim neighbors; our religion does not stop our cooperation in our lands, tending our sheep or feeding our chickens,” the man speaks, his face pulsing with a smile like a robe that warms the world with his reassurance.

Multiple languages spoken in “Sarmsakh Tahtani”

The people of Sarmsakh Tahtani experience linguistic and religious diversity in a harmony where it is difficult to distinguish between a Syriac Christian and a Muslim Kurd. It is a difference that defeated extremism and its darkness, and paved the way for linguistic and religious pluralism in the face of the one solid color that successive political regimes worked to build its high walls.

Wadih, adjusting his headband, says: “We have spent seventy years in this village with five other Syriac families. We speak Kurdish since we were born, and sometimes I speak Arabic with my son, Danny, and my wife. The language difference does not change our support for each other if something urgent happens, our languages are our intentions.”

The language of love is universal. It is communicated by feelings that make us to be fluent in it; a language with the same alphabet and meanings.

Shared holidays

Thanks to their coexistence, the people of Sarmsakh Tahtani gather during the days of ease and hardship; they celebrate four religious holidays as if they were one. The Christians of the village celebrate with the Muslims in feast rituals. Because their differences do not halt their brotherhood. “Our differences in religion made us distinguished from others by the fact that we celebrate four holidays a year. We paint eggs together at Easter. Sometimes I tell myself that the difference in the date of our festivals brings joy to us all by recurring them in one year, away from the hardships of life and the emigration of eight of my sons to European countries,” Wadih adds softly.

Differences do not change practice of religion

The image of love and the difference in the form of Sarmsakh Tahtani has not changed. Mikhail, one of the villagers, contributed to building the village mosque when he collected money to cover its expenses, and its cost at the time amounted to about one hundred thousand Syrian pounds. Today, the mosque hosts mourning ceremonies as well; Christian George Shamoun, a resident of the village, used to recite the Qur’an in Islamic funerals. This difference did not constitute a barrier between the villagers, and none of the villagers objected to the nature of this divine will. His smiling face turning into impatience, Wadih says: “I wonder why the extremists call for spreading murder and displacement in the world out of religion. The practice of religion and God’s love for all, and our differences in religions will not change our spiritual relationship with the Lord.”

Wadih Iskandar lives in Sarmsakh Tahtani, in peace with his Syriac and Kurdish neighbors. Like the rest of the villagers, he takes care of beekeeping, makes grape raisins, and carefully trims the olive trees until the time they are harvested. They share when the earth replenishes them with its abundance. It is the Islamic-Christian union that gives the village its splendor. Everyone is busy in their daily affairs, where there is no time or room for hatred. As for extremism and hatred, there is another space on the other side of this quiet world, where there are still extremists weaving tents for refugees, and causing farewell tears.